The Talkies Arrive

-

.jpg)

La Patrie, 22 September 1930, p.5

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

.jpg)

La Patrie, 9 December 1930, p.8

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

-

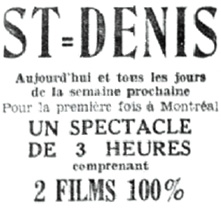

Le Petit Journal, 11 January 1931, p.23

Source : Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec

Modest Beginnings

The world’s first talking film is usually identified as Alan Crosland’s The Jazz Singer, released in October 1927, in which a few words can be heard distinctly, in addition to the film’s half-dozen songs. In reality, most of the film’s dialogue was found in intertitles, like in silent film. Nearly three years would pass before the talkie became truly established almost everywhere.

A Lot of Technology to Invent

The talkie posed a number of technical problems, from cumbersome recording equipment and an often screechy sound quality to the existence of several competing systems, the difficulty of synchronising sound and image, the fact that studios were not soundproof, etc. The cost of producing and exhibiting sound films also increased significantly. Movie theatres had to install sound systems and new projectors.

In production studios, the transition from silent to talking films did not occur overnight. Initially, music and sound effects were added to many films shot during the final years of the silent era. Others were shot with a synchronous sound track, but without words. Finally, the soundtrack came to include every element we are familiar with today. In the early years of the talkie, many films were distributed in two versions: a silent version and a sound or talking version. After 1932, cinemas were provided with talkies alone.

When Warner Bros. launched The Jazz Singer, it used the Vitaphone technique, which consisted of a sound track recorded on disc and synchronised with the image. This technology was not practical to use, but it gave the best quality at the time. It disappeared a few years later, yielding to technology such as Photophone or Movietone, which made it possible to photograph sound waves directly onto film. These techniques eliminated the problem of synchronisation, but had the drawback of taking up a significant portion of the film’s image track. The film image thus became almost square during the early years of the talkies until the space occupied by the sound track on the film was successfully reduced.

A New Aesthetic

The arrival of the talkie didn’t just bring dialogue—it significantly transformed film aesthetics. The camera could no longer be moved in the same way and ambient sounds had to be taken into account. The disappearance of intertitles modified the film’s rhythm and transitions between sequences. Acting styles were obliged to change. While silent cinema relied mostly on miming, with Chaplin its unmatched genius, the talkie was most often compared to theatre. Actors had to invent a new physical style while at the same time learning to speak more elaborate lines. Attention to the aesthetics of sound became indispensable, like attention to the aesthetics of the image before it. A good many careers came to a halt, as the film Singin’ in the Rain (Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, 1952) depicted so well twenty years later.

And Music Too . . .

Silent movie orchestra or pianists were able to provide sound effects or a musical rhythm and suggest various emotions without any interruption, or very little, of the action. In the talkies, music needed only to inspire the inner resonance of the drama or comedy. In the beginning many films overused music, but soon the dramatic merits of silence were discovered. The musical comedy also soon established itself as a major genre.

The new technology standardised the film product. Henceforth, there were practically no more local variations: viewers heard the same thing around the world. The power and influence of the Hollywood majors were thereby reinforced.

Hollywood Becomes Multilingual

Another effect of the arrival of the talkie was that Hollywood studio bosses quickly realised that their domination of world cinema would not last if they did not provide versions of their films in the principal languages of the many countries in which they were screened. Dubbing was introduced in 1932, but used only sparingly, and it did not become widespread in Quebec until 1943.

In the meantime, beginning in 1930, Paramount began to produce versions of its films in a variety of languages, at first in Hollywood and then in modern studios it built in Joinville, a suburb of Paris, where actors speaking a range of languages came to act out the same script on the same set. After a few years, however, Paramount abandoned this manner of internationalising cinema, deeming it too costly.

Meanwhile, in Montreal

During the so-called “silent” film era in Montreal, several devices made it possible, at least in theory, to project animated views with synchronous sound tracks. These devices had major drawbacks, however, rendering their success fleeting at best. Their subjects were limited by the production conditions, the synchronisation was capricious, the sound volume insufficient, etc.

The first Canadian movie theatre to definitively make the transition to the talkies in the late 1920s was the Palace on St. Catherine St. in Montreal. On 1 September 1928, it showed Frank Borzage’s Street Angel, a film with a few spoken scenes, musical accompaniment and synchronous sound effects.

In the fall of 1928, the Palace presented a new sound film each week, making it the most popular cinema in Montreal. The city’s film buffs were able to see The Jazz Singer there on 1 December. On 5 January 1929, it presented its first “all-talkie” film, Roy Del Ruth’s The Terror. A few weeks later, on 9 February, it presented what appears to be the first talkie shot in Quebec, a Fox newsreel showing the opening of the National Assembly, with a speech in French by Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau.

Sound Film Everywhere in the Province

It was not until four months after the premiere of Street Angel at the Palace that a second Montreal movie theatre, the Capitol, converted to sound. In the spring and summer of 1929, the majority of large and medium-sized cities in Quebec saw the arrival of cinemas equipped to show talkies, especially those associated with one of the large chains (Famous Players, United Amusement, Confederation Amusements). A brand-new cinema in Sherbrooke, the Granada, was designed for talkies and began showing sound films in February 1929. The Premier cinema in that same city also began screening talkies in October. In Quebec City, the Empire converted to sound in March and the Canadien and the Auditorium in May. In Trois-Rivières, the Imperial converted to sound in April and the Capitol in June. In Montreal, even neighbourhood cinemas such as the Rivoli or the Corona joined in. New cinemas were built during this period, such as the Seville, the Outremont and the Granada, and were of course equipped for sound.

Theatre Programs Remain Diverse

While the talkie transformed the film experience, it didn’t completely alter the program offered by the theatres. Many of them, including some of the largest, such as the Loew’s in Montreal, continued to present vaudeville acts in English and different forms of stage entertainment in addition to the film. The equivalent in French took place at the Arcade theatre in the city’s east end.

Throughout this period, the Roxy, the “home of the silent film” and of “art cinema”, as its publicity proclaimed, was practically the only theatre to show anything other than American cinema. Carl Theodor Dreyer’s film La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc was screened there in June 1930. The theatre’s owner, Charles Lalumière, was slow to take up the new fashion. He continued to exhibit a variety of silent films, from India, Germany, England and France, screening them when possible with French intertitles. He converted to sound in late 1930 with the French film Toute sa vie, produced by Paramount. In early 1931 Robert Hurel of France-Film purchased the Roxy and re-named it the Cinéma de Paris. After it opened on 14 February of that year it became the premier venue for French cinema for a decade.

French producers were late converting to talking films. The first French talkie wasn’t made until 1929, when André Hugon shot Les trois masques. And even then he made it in England, which had better sound equipment at the time. As soon as the film was made available, Jos Cardinal, who had been managing the Théâtre Saint-Denis since 1925, took it on and gave his theatre a new vocation. It was screened there on 31 May 1930. This date marks the true arrival of the spoken French language on Quebec’s movie screens.